-

Twenty-Five is a celebration. A celebration of the past quarter century with each year represented by the work of an artist who made an exhibition at our gallery in that year. 25 works by 25 artists to celebrate our 25th birthday, and then a few more by others who have played a part in our programme since we first opened our doors in 1998, because… well, because we can, and because it seems a shame not to include others who are close to our hearts.

1998 was a good year in Scotland. It was the last time the Scottish football team made it to the world cup finals, opening the tournament with a game against Brazil which we lost, obviously, but without disgrace. Back home, the Scotland Act was passed following a positive vote for devolution the previous year, and alongside the parliament that was being built in Edinburgh came a new confidence and internationalism. It seemed like a promising moment to open a gallery that would aim to represent Scottish artists internationally and bring international artists to Scotland.

25 years later there have been ups and downs, fabulous moments, and hideous ones, but we’re still here and we’re grateful to so many people who have joined us on the journey. Collectors of course, some of whom have become close friends, colleagues in the industry and closest to home, the gallery team. They are, and always have been down the years, a diverse and wonderful group of human beings with whom we are lucky to spend our days. Mostly though, we’re grateful to the artists with whom we’ve been lucky enough to work. Many of them have now been in our lives for a quarter of a century. And without them, quite obviously, there would be nothing to celebrate and no story to tell.

-

1998

We opened the gallery in the summer of 1998 on the ground floor of a building that was also our home. We had two tiny daughters, Molly and Edie (unfortunately both afflicted with chickenpox on the day of the opening) a paucity of experience, and a first show that we titled, imaginatively, Opening Exhibition. It showcased a small group of Scottish artists whose work was seldom seen at home, including Callum Innes, Craigie Aitchison and of course Ian Hamilton Finlay. Ian’s position as an artist at the forefront of the European avantgarde (despite his never leaving his home in the Pentland Hills) was an inspiration for a gallery from Scotland with aspirations to develop an international reach.

Ian’s work has been a part of our lives ever since, and in our current premises at the Glasite Meeting House we have a permanent display of his prints and paper works in the building’s original kitchen - the kitchen being at the heart of things and where we think Ian would almost certainly have been most comfortable. For Twenty-Five this display is joined by a sculptural work with an appropriately domestic twist. Matisse Chez Duplay takes the form of an open wooden cabinet in which hang 20 ceramic mugs, each bearing a line from the Alphonse de Lamartine’s French Revolutionary memoir ‘History of the Girondists’: The chamber of the deputy of Arras contained only a wooden bedstead, covered with blue damask ornamented with white flowers, a table and four straw-bottomed chairs. A depiction which might recall an interior by Matisse, but which in fact describes Robespierre’s room in the house of Maurice Duplay, the cabinet maker who gave him shelter from the authorities, and in so doing pitched a simple life into the disorder of the day.

-

Ian Hamilton FinlayMatisse chez Duplay, 1990ceramic and wood, with Julie Farthing101.5 x 80.5 x 13.5 cm

Ian Hamilton FinlayMatisse chez Duplay, 1990ceramic and wood, with Julie Farthing101.5 x 80.5 x 13.5 cm

40 x 31 3/4 x 5 1/4 in -

1999

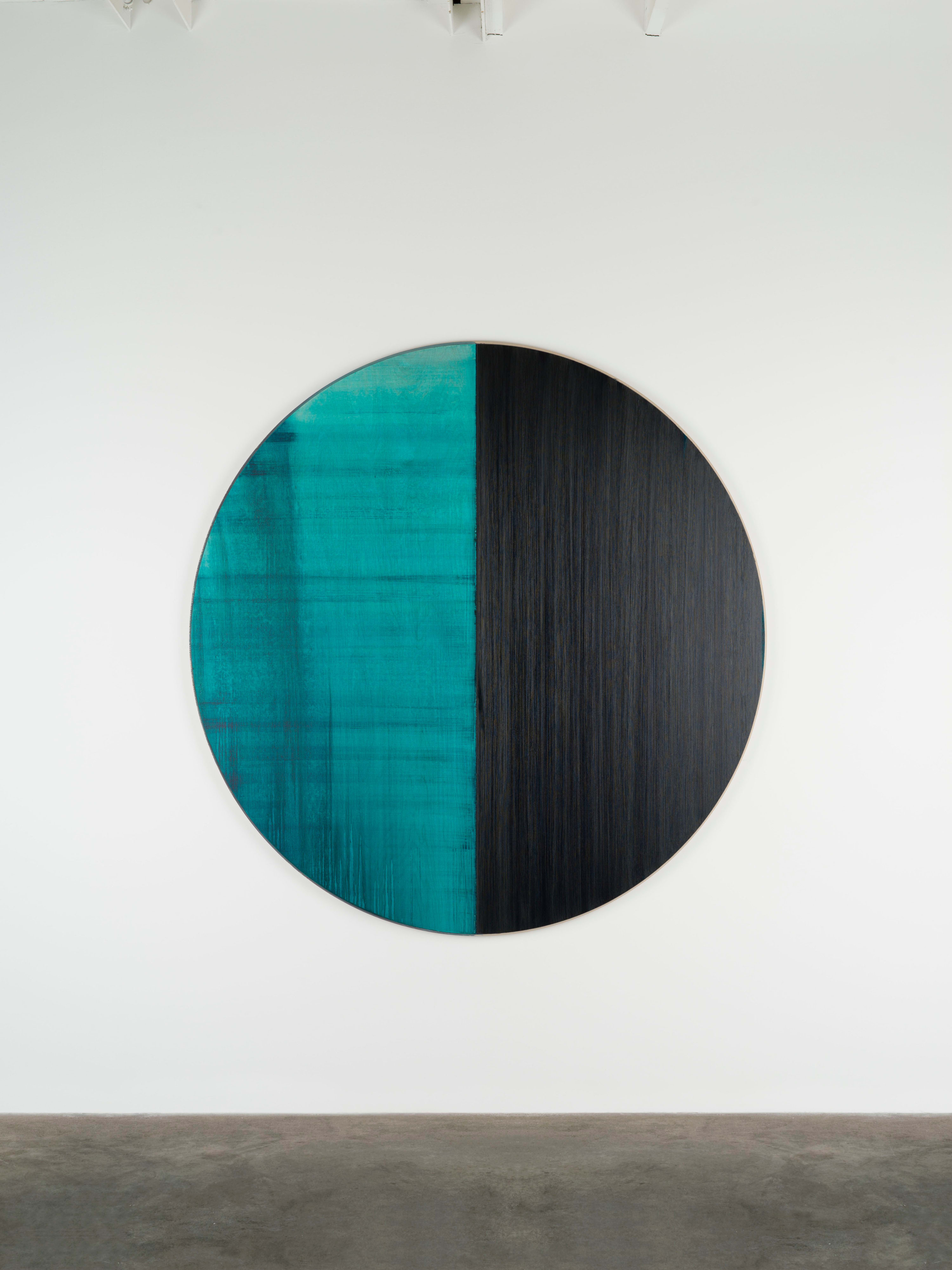

Like Finlay, Callum Innes took part in our very first exhibition in July 1998 and, like Finlay, he is an artist who has chosen to stay in Scotland, despite building his reputation across the world. Callum’s friendship and support have been hugely important to us over the past 25 years during which time we have made six solo exhibitions, beginning with our first for the Edinburgh Festival in 1999. We look forward to the seventh. For Twenty-Five we are exhibiting one of his newest series of works, a ‘tondo’ painting made on a (not quite) circular plywood panel. A further development the unique language of abstraction that he has explored for 30 years, based on the play of additive and subtractive processes, but with a new materiality offered by the grain of the wood and correspondingly subtle shifts in the physicality of the work itself.

-

Callum InnesUntitled, 2022Oil on Birch Ply180 x 175 cm

Callum InnesUntitled, 2022Oil on Birch Ply180 x 175 cm

70 7/8 x 68 7/8 in -

2000

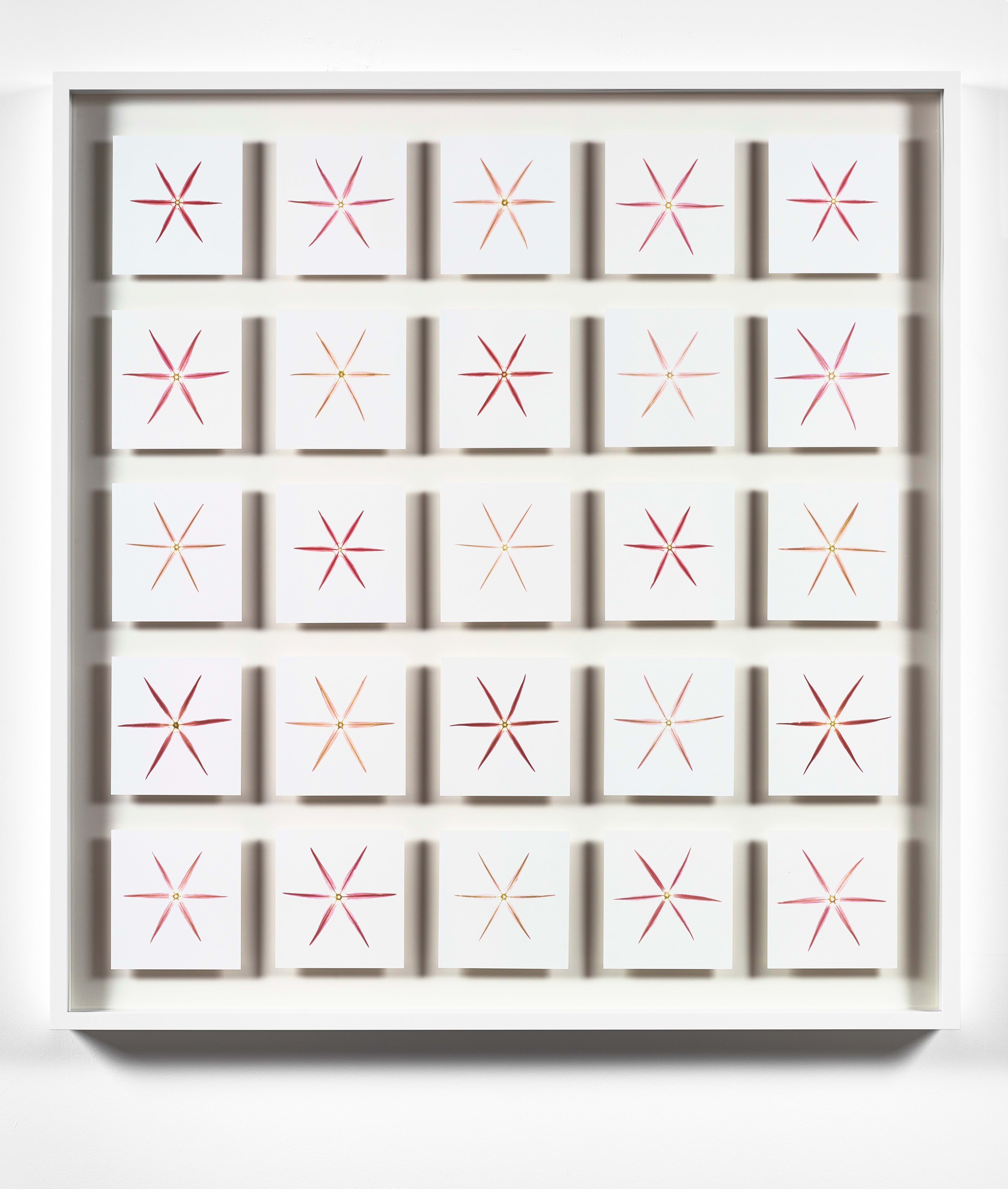

Garry Fabian Miller’s earliest camera-less photographs looked to the pioneers of photography in the 1830s, by passing light through translucent material such as leaves and flowers onto light sensitive paper. This starting point, steeped in the natural world, has remained vital across his 40-year career as he has explored the more abstract forms of picture making for which he has become so well known.

Nature though remains at the heart of his practice with works like Agnes Alium, exhibited here, offering an almost autobiographical self-measuring across time, and a rootedness in place which owes a great deal to a life lived on Dartmoor and a daily routine of walking and watching the rising and setting of the sun. Our first show together was in 2000, since when we have worked together on half a dozen exhibitions and related publications, including most recently Blaze which marked the end of an era as his analogue photographic materials became extinct in the digital age. This spring will see a major exhibition and publication ADORE at the Arnolfini in Bristol and the publication of his memoir Darkroom, by the Bodleian Library.

-

Garry Fabian MillerAgnes, Allium, Homeland, June 2011flower, light, 25 unique dye destruction prints20.3 x 19 cm

Garry Fabian MillerAgnes, Allium, Homeland, June 2011flower, light, 25 unique dye destruction prints20.3 x 19 cm

8 x 7 1/2 in (each print)

133.2 x 139.2 x 7 cm

52 1/2 x 54 3/4 x 2 3/4 in (framed) -

2001

2001 saw our first exhibition with David Austen, another artist with whom we continue to work closely over 20 years later, and whose project The Boys: an adventure, a collaboration with the author Hisham Matar, will be shown in the gallery this spring. David is a polymathic magpie - gathering ideas for his paintings, drawings, sculpture, and films from a deep knowledge of literature and art history. The linking of word and image is a constant in his work, as is the teasing of unlikely connections between seemingly unrelated elements to make something that seems, well, just right.

-

David AustenLittle Ocean (red) and Sailor , 2022oil on flax canvas (diptych)30.5 x 25.4 cm

David AustenLittle Ocean (red) and Sailor , 2022oil on flax canvas (diptych)30.5 x 25.4 cm

12 x 10 in (each canvas) -

2002

2002 was quite a year, our fifth as a gallery and one that involved some extreme juggling of our cohabiting domestic and professional worlds. In the summer we exhibited important paintings by Agnes Martin and Ellsworth Kelly alongside antiquities from Anatolian, Babylonian and Bactrian times. More importantly a third daughter, Esme, was born. Later in the year we made an exhibition with Eduardo Chillida, his first ever in Scotland, and the last held anywhere during his life. It was sold, almost in its entirety, to the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich. 2002 was also the first time that we exhibited work by our dear friend James Hugonin, another artist who as stayed with us on the journey ever since, a remarkable figure who makes on average a single painting each year.

Together we have seen the culmination of three series of works over two decades, each of which further pushed the possibilities of his chosen form in which small marks of colour are applied across an underlying grid. We showed the most recent series, the Elliptical Form paintings, early last year and have been waiting in eager anticipation to see what comes next. And here they are, the first works in a new direction: an extraordinary new diptych in which the grid tales a step back and the interior musicality that has always been in his paintings moves even further to the fore.

-

2003

Craigie Aitchison was another important figure in the early days of the gallery. Like Finlay and Innes he took part in our opening exhibition in 1998, but it wasn’t until the summer of 2003 that we held a solo exhibition. Craigie took some convincing to show his work in Edinburgh – his relationship with the place being one of unforgiving animosity forged by the deeply conservative circumstances of his childhood and what he still felt, a half a century later, as the dismissal and disapproval of ‘Edinburgh folk’. The process of persuasion took many afternoons at the wrong end of a vodka bottle before he agreed to take part in our first exhibition, but over the years we worked together, until his death in 2009, we were proud to play a small part in reconciling his relationship with the country of his birth.

-

Craigie AitchisonBoy Seated with Crucifixion, 1985oil on canvas

Craigie AitchisonBoy Seated with Crucifixion, 1985oil on canvas

171.4 x 143.5 cm

67 1/2 x 56 1/2 in (canvas) -

2004

2004 was a year of mixed fortunes. Half-way through the year dry rot, the scourge of historic buildings, came to visit. But necessity is the mother of invention (and slightly suspect exhibition titles) and so came From Here to Eternity – later dubbed ‘Vermeer to Eternity’ by Roger Ackling, a show that included the first showing in Scotland of works by Vija Celmins and James Turrell – the Turrrell light projection Prado Red requiring a room to be built within the room to mask construction work going on behind the walls. It was also the year in which we made our first exhibition of works from Ellsworth Kelly’s print archive and our first exhibition with Thomas Joshua Cooper.

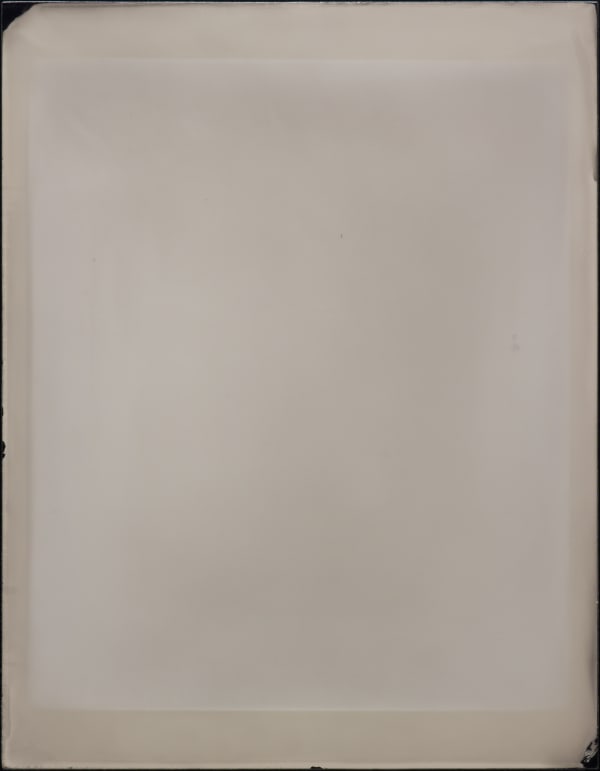

Thomas is a self-styled ‘expeditionary artist’ working exclusively with an adapted wooden box camera from 1898 and crossing the globe in search a location always chosen on a conceptual premise, rather than any sense of how the place might look. At some of the more extreme sites, such as in this almost ghostly image looking South from the South Pole in temperatures of -41.6°C, the journey itself may take several weeks, but when he gets there, he makes a single exposure. A solitary image that may or may not succeed. There’s a perversity to this which suggests that despite using the tools of photography, he’s not really a photographer in any conventional sense, rather he’s a kind of artist-explorer driven by faith and wilful determination.

-

Thomas Joshua Cooper-43ºf / -41.6ºc, The Polar Plateau - The South Pole, Antartica, 2007-08silver gelatin print, hand toned and printed by the artist.

Thomas Joshua Cooper-43ºf / -41.6ºc, The Polar Plateau - The South Pole, Antartica, 2007-08silver gelatin print, hand toned and printed by the artist.

This print is AP1 from an edition of 3.70 x 100 cm

27 1/2 x 39 3/8 in (print)

106.5 x 141.5 x 3.5 cm

41 7/8 x 55 3/4 x 1 2/5 (framed) -

2005

Talking of faith and determination, there are few artists of recent times who have channelled these as determinedly as Sean Scully. We first showed Sean’s work in 2001 and made a second solo exhibition in 2005 alongside which we published the text of a lecture given by Sean at IVAM, Valencia, the first time that his writings had been published in book form. This led, the following year, to Resistance and Persistence a full volume of Sean’s selected writings, edited by Florence and launched with a display at the National Galleries of Scotland. The title was taken from his essay on Giorgio Morandi, but the sentiment applies in equal measure to Sean himself and was indeed used ten years later as the title of a major exhibition of his work in China. Fire is a magnificent example of art’s ability to communicate emotion through abstraction. It’s a painting with a powerful sense of contained light, sombre at first, but with an inner radiance that seeps through the cracks between the blocks of colour, suggesting an undercurrent of energy and hope.

-

Sean ScullyFire, 2006Oil on linen160 x 160 cm

Sean ScullyFire, 2006Oil on linen160 x 160 cm

63 x 63 in -

2006

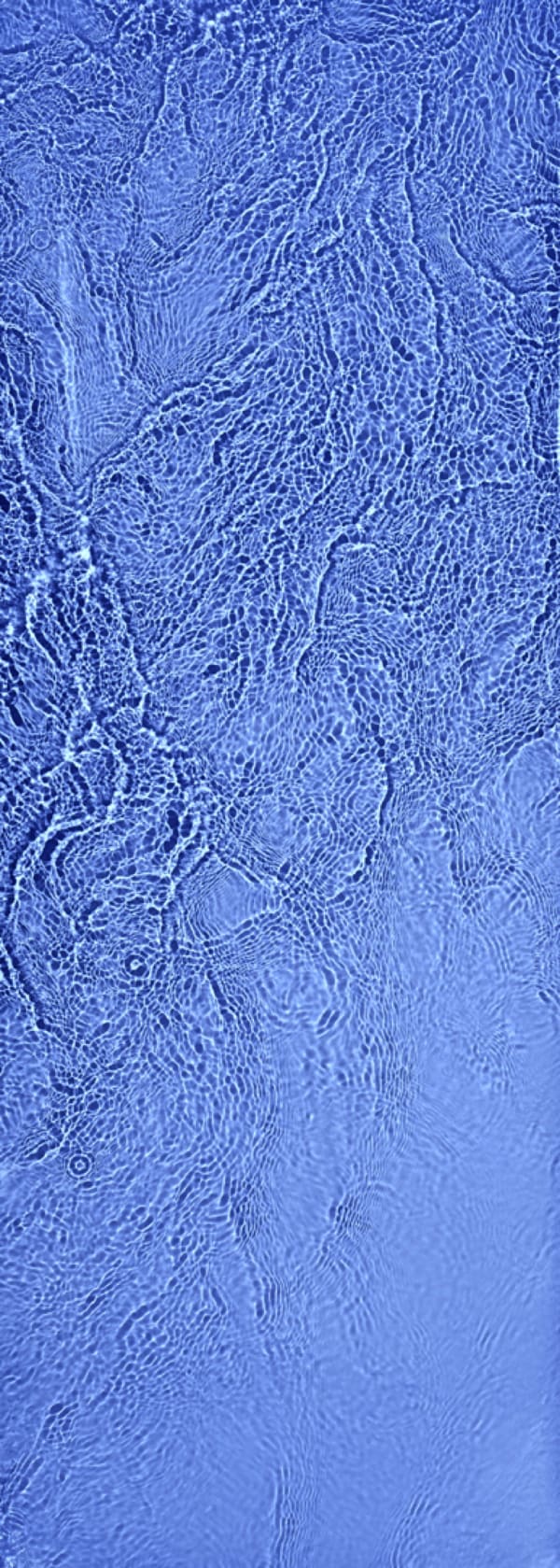

Like Garry Fabian Miller and Thomas Joshua Cooper, Susan Derges looks to the history of photography to explore new ways of picture making in the present day. We first showed her work in 1999 alongside the aerial photographer Patricia Macdonald and made solo shows in 2002 and 2006 which focussed on her work made at night on the river and at the edge of the sea – works which have something of the micro and macrocosm about them – simultaneously offering a close-up of life, and a sense of something viewed from the edge of space. In recent years, as her original, analogue materials have become extinct, she has pursued new ways of making images in the digital age, but her focus has remained firmly fixed on the natural world, allowing her to act as she has described ‘as a channel through which natural events can be made visible’.

-

-

Susan DergesCascade i, 2020Fujicolour crystal archive print

Susan DergesCascade i, 2020Fujicolour crystal archive print

Edition 2 of 2170.6 x 66.5 x 4.5 cm

67 1/8 x 26 1/8 x 1 3/4 in

(framed) -

Susan DergesCascade ii, 2020Fujicolour crystal archive print

Susan DergesCascade ii, 2020Fujicolour crystal archive print

Edition 2 of 2170.6 x 66.5 x 4.5 cm

67 1/8 x 26 1/8 x 1 3/4 in

(framed) -

Susan DergesCascade iii, 2020Fujicolour crystal archive print

Susan DergesCascade iii, 2020Fujicolour crystal archive print

Edition 2 of 2170.6 x 66.5 x 4.5 cm

67 1/8 x 26 1/8 x 1 3/4 in

(framed)

-

-

2007

We started working with Peter Liversidge in the summer of 2006 when we invited him to make an offsite project in Edinburgh during the city’s annual arts festival. Some weeks later a letter arrived: a proposal – ‘I propose to walk people’s dogs’, the next day another ‘I propose to run a dentist surgery from the gallery to provide free dental care for the festival goer.’ And so on, until 105 proposals later it became clear that this was the work Festival Proposals – the first of many such volumes that have appeared in the years since.

Our first gallery-based exhibition followed the next year in 2007, but the work included here is a memory of that first project, one of the rare proposals that suggested an artwork rather than a performance or idea. In this case a yellow neon based on a phrase that jumped out of the dictionary as he thumbed through its pages checking the spelling of a word in the previous proposal.

-

2008

By 2008 the gallery had outgrown the townhouse on Carlton Terrace. The rooms were beautiful, but frustratingly full of architecture: doors; windows; fireplaces and so forth, and the line between domesticity and professionalism ever harder to distinguish. We found a former warehouse on Calton Road at the back of Edinburgh’s main train station and set about turning it into 6,000 sq ft of purpose-built gallery.

Our heads were full of our own plans, and we weren’t paying very close attention to the wider world. We opened, with spectacularly bad planning, just in time for the financial crash. The first exhibition in the new space was Kay Rosen’s Huen, a word that doesn’t exist, except as an invented amalgam of two others – hue and hewn – a typically precise gesture of imprecision to describe a body of work ‘shaped from colour’. Rosen’s love of colour is second only to her love of language and much of her work harnesses both to make visible the things we would otherwise miss. As so often in Rosen’s work the clue to the seemingly obscure choice of words in the present work hat / omen / ant is made obvious by the title - the three missing w’s hiding a hidden statement of feminist intent.

-

Kay RosenWhat Women Want, 2020enamel paint on canvas78.7 x 54 cm

Kay RosenWhat Women Want, 2020enamel paint on canvas78.7 x 54 cm

31 x 21 1/4 in -

2009

We’ve shown Francesca Woodman’s work on several occasions, most recently alongside Zanele Muholi, Cindy Sherman and Oana Stanciu in 2019, but it was ten years previously in 2009 that we made a solo exhibition of her work. In 2011 a few works were included in Hiding in Full View an exhibition of paintings by Alison Watt exploring ideas of presence and absence, for which the poet Don Paterson wrote a sonnet on Woodman which appeared as fragments of text on the walls of the gallery. One of these fragments seems especially appropriate: ‘We don’t exist – we only dream we’re here – This means we never die- We disappear’.

-

Francesca WoodmanUntitled, New York, 1979-80Gelatin silver estate print

Francesca WoodmanUntitled, New York, 1979-80Gelatin silver estate print

Edition 5/40

(FW 667)13.3 x 13.3 cm

5 1/4 x 5 1/4 in

-

2010

The Brazilian artist Iran do Espírito Santo first entered our life in 2009 when he took part in our exhibition Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing alongside Cornelia Parker and Francis Alÿs, whose work gave us the title for the show. Our first solo exhibition of Iran’s work followed in 2010 (his first ever in the UK) and remains one of our favourite of all the exhibitions staged at the Calton Road gallery. For nearly a month Iran and his team worked in the space transforming the entire gallery through a series of wall paintings in a subtly shifting gradient of greys. It was initially intended as a backdrop to his sculpture, such as the work exhibited here, but having finished the wall paintings it looked so spectacular we decided to leave the space empty. In these sculptures Iran shifts the scale and material of seemingly ordinary things to reveal a paradox that gets to an essential truth about the form of an object, whilst completely divorcing it from any connection to its apparent function.

-

Iran do Espírito SantoDropping Bottle, 2013Granite

Iran do Espírito SantoDropping Bottle, 2013Granite

Edition of 5 +2 APs. This is AP 1/262 x 22 x 22 cm

24 3/8 x 8 5/8 x 8 5/8 in -

2011

We were first introduced to Winston Roeth by our friend Callum Innes twenty years ago, and both artists took part in very different exhibitions about colour in the first decade of the gallery’s life: a self-explanatory exploration of the monochrome White in 2003 and its more jaunty cousin Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue? in 2005. We held solo shows of Winston’s work in 2006 and 2011, the year that he represents here. It is maybe a bit perverse of us to represent one of the greatest colour painters with whom we have ever worked with a grey and black drawing, but when we saw this exquisite early work from 1990 on a recent visit to Winston’s studio in Beacon, we couldn’t resist.

-

Winston RoethLandscape Drawing, 1990Pastel on Rives BFK paper48.9 x 65.1 cm

Winston RoethLandscape Drawing, 1990Pastel on Rives BFK paper48.9 x 65.1 cm

19 1/4 x 25 5/8 in

(paper)

63 x 79 x 4.5 cm

24 3/4 x 31 1/8 x 1 3/4 in

(framed) -

2012

Our first contact with Kevin Harman was through a solicitor, a call that came out of the blue asking if we would be prepared to speak in support of an artist whose degree show had got him into a spot of bother with the police. The offending project, Love Thy Neighbour, involved the temporary appropriation of doormats from outside peoples’ front doors of Edinburgh tenements. In Kevin’s words: ‘I had a massive suitcase and I started going into all the stairwells and taking all the doormats, until I had about 220 of them, and I took them down the Edinburgh College of Art and laid them down as a kind of pathway across the sculpture court… then I went back and posted letters and put up posters saying if you’ve lost your doormat, here’s what’s happened to it, and inviting them to come to the degree show, have a glass of wine, meet their neighbours and admire their mats and everyone else’s in this sort of tapestry’. Needless to say, some of the residents weren’t impressed, hence the involvement of the police.

Kevin continues to make work in all sorts of ways, often using reclaimed materials, although fortunately they are mostly of the found rather than ‘borrowed’ variety. His most significant ongoing series are the ‘glassworks’ – gloriously physical abstract paintings made from recycled household paint in salvaged double-glazing window units.

-

Kevin HarmanWizards High On Magic, 2021Household paint, double-glazing unit, steel frame143 x 91 x 6 cm

Kevin HarmanWizards High On Magic, 2021Household paint, double-glazing unit, steel frame143 x 91 x 6 cm

56 1/4 x 35 7/8 x 2 3/8 in -

2013

Frank Walter, or Francis Archibald Wentworth Walter to give him his full name, self-styled 7th Prince of the West Indies, Lord of Follies and the Ding-a Ding Nook, arrived in our life as a complete surprise. We were introduced to his work by the art historian Barbara Paca in 2012, and made our first exhibition of his work, alongside Forrest Bess and Alfred Wallis the following year. In that moment no work of Frank’s had ever been exhibited anywhere, or indeed offered for sale in a gallery setting, but in the ten years since, Frank’s star has risen fast, establishing his place as one of the most distinctive Caribbean artists of the past 50 years.

There have been exhibitions at the Venice Biennale in 2017, where Paca curated Antigua and Barbuda’s first ever pavilion with a show of his work, followed by a major museum exhibition at MMK Frankfurt in 2020 and exhibition at David Zwirner in London and New York and at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels. Our own exhibition Music of the Spheres for the Edinburgh Art Festival in 2021 presented the first exhibition of his so called ‘spool’ paintings – the circular tondos that are amongst the most visionary paintings of his career.

-

Frank WalterUntitled (Green land, blue-green sky)oil on biocomposite material, backed with Masonite22.4 cm diameter

Frank WalterUntitled (Green land, blue-green sky)oil on biocomposite material, backed with Masonite22.4 cm diameter -

2014

We first showed Katie Paterson’s work in 2011 in the exhibition Mystics or Rationalists, a title taken from Sol LeWitt’s sentence - ‘Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions that logic cannot reach’. Her work was shown among other artists (including Susan Hiller, Cerith Wyn Evans, Ceal Floyer and Simon Starling) whose work invites the viewer to make a leap of faith between an idea and the resulting object. In Katie’s case the context was perhaps a bit misleading as her work, although deeply poetic, and often beyond the realm of logic, does not really belong to the mystics, being based on serious scientific research, and often realised with the help of expert astronomers, geologists, botanists and biologists. Hard science in other words, given an imaginative and sometimes romantic twist, as we see in this present work (a new photograph shown here for the first time) in which the artist is pictured casting a drop of water into the Godafoss waterfall in Iceland. Suspended within the droplet was a map of the entire universe, encoded into DNA, a map of everything known, now hidden forever in the depths of the ocean.

-

Katie PatersonWater drop, 2022hand-touched silver gelatin print

Katie PatersonWater drop, 2022hand-touched silver gelatin print

edition of 10 with 2 APs. This is #1.100.2 x 134.4 x 4.5 cm

39 1/2 x 52 7/8 x 1 3/4 in (framed) -

2015

Charles Avery was an early visitor to our first gallery on Carlton Terrace, brought to our door by curiosity having grown up in a house a few doors down the street. He told us that he was embarking on an epic project of visual and philosophical invention that would consume the rest of his life – an immersive fictional world called The Islanders. We thought he was deeply engaging though probably a bit mad, and so looked the other way. More fool us. A few years later he was representing Scotland at its first pavilion in Venice and although it took us a few years to catch up with the genius of his imagination, we have now made two exhibitions that take their place in the Island story - The People and Things of Onomatopoeia in 2015 and The Gates of Onomatopoeia in 2019. In recent months the drawings that have always formed the narrative backdrop for his ideas have been joined by paintings on canvas, such as the one exhibited here which are adding new layers of richness and texture to a world that is at once a both familiar and strange.

-

Charles AveryUntitled (couple with pet - green eyed girl), 2023acrylic on linen122.6 x 82.6 cm

Charles AveryUntitled (couple with pet - green eyed girl), 2023acrylic on linen122.6 x 82.6 cm

48 1/4 x 32 1/2 in (framed) -

2016

We have made several exhibitions with Jonathan Owen over the years, but the show held in 2016 was especially important, being the moment in which we found ourselves temporarily back at our original location on Carlton Terrace, having given up the gallery on Calton Road. We’d spent nine years in that space making beautiful exhibitions, publishing prints, running film clubs, staging performances and public art projects – trying everything we could muster to engage a wider Scottish audience. But it didn’t really work, there was an audience of course, but not one with the means or inclination to support the essential activity of a private gallery. In retrospect, we’d been behaving more like a publicly funded space… but without the funding. Financially bruised and emotionally a little battered we retreated to Carlton Terrace to consider the future. But the exhibitions never stopped, and the first show we made in the new world order was timed to coincide with Jonathan Owen’s major commission for the Edinburgh Art Festival in the Burns Monument on the edge of Calton Hill. It was his first life-sized figure, which now resides in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne.

In common with all his work, the raw material for that sculpture, was a piece of antique marble statuary, an object once suggesting ideas of permanence and power which had become irrelevant and almost invisible over time, but which, in Jon’s hands, was transformed into something new. His is a way of working that seems especially pertinent in the present moment when the conversation around public monuments is being actively reassessed.

-

Jonathan OwenUntitled, 202319th Century marble bust with further carving69 x 43 x 24.5 cm

Jonathan OwenUntitled, 202319th Century marble bust with further carving69 x 43 x 24.5 cm

27 1/8 x 16 7/8 x 9 5/8 in -

2017

By 2017 our sights were set on a new gallery space, the historic ‘Glasite Meeting House’ on Barony Street, a glorious building that had been mothballed for over 30 years. Our partner in bringing the building back to life was the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust, but its category ‘A’ listing meant that the wheels of planning were turning slowly, and so we found ourselves with a problem. A year empty of programming. A problem within which lay an opportunity, in the shape of a circular series of short exhibitions, each pairing two works by unrelated, but somehow connected, artists - beginning with Mark Wallinger’s film ‘The End’ (what better place to start) and closing with his ‘Angel’. It was a terrific sequence involving such diverse pairings Ragnar Kjartansson’s film ‘A Lot of Sorrow’ sandwiched between a still life by Giorgio Morandi and a C15th altarpiece of St Sebastian.

We’ve chosen to represent that diverse year with a pair of Richard Forster’s meticulous graphite drawings. These have been described, including by the artist himself, as a kind of ‘photocopy realism’. It’s a rather prosaic phrase for quite extraordinary works which seem to belong outside the time and place in which they were made.

His subjects are often archival, sourced from books, magazines and the internet, and focus on the meeting of architecture and moments of social change. In recent projects he has been especially drawn to the socio-political history of the former east Germany and the more recent phenomenon of ‘ostalgie’ – a kind of nostalgia for life under Communist rule. The diptych featured here shows the Stadtschloss in East Berlin, destroyed in the aftermath of the November Revolution of 1918.

-

Richard ForsterNotes on Architecture: Site of the Former Peoples' Palace, Berlin (diptych), 2016pencil and acrylic on card33.4 x 24.6 cm

Richard ForsterNotes on Architecture: Site of the Former Peoples' Palace, Berlin (diptych), 2016pencil and acrylic on card33.4 x 24.6 cm

13 1/8 x 9 3/4 in (each frame) -

2018

We opened the new gallery in May with a glorious exhibition of five very large paintings by Callum Innes. The gallery immediately felt like home and has proved the perfect base from which to strengthen our mission of showing the best of Scottish art in an international context. The way that you meet artists is always interesting, or at least it is to us, especially when the introduction comes from another artist. Back in 2013, when we first showed Frank Walter’s work, we met Peter Doig who got in touch asking about this artist from the Caribbean who thought he was Scottish… his own position in reverse. We asked Peter how he’d heard about Frank and it turned out that he’d been told about him by his friend Andrew Cranston. Soon after we went over to Glasgow to meet Andy and were bowled over by a studio filled with gorgeously intense little paintings, mostly on the covers of old hardback books. We made a small show together soon after and in 2018 hosted a much larger exhibition as one of the earliest shows in the Glasite Meeting House. We are looking forward to making a new exhibition, and working on a new book, for this coming summer.

-

Andrew CranstonSomething of the Night, 2021distemper on canvas180 x 210 cm

Andrew CranstonSomething of the Night, 2021distemper on canvas180 x 210 cm

70 7/8 x 82 5/8 in

(Sold) -

2019

David Batchelor took part in an exhibition titled Thread in 2006 alongside Carl Andre, Cornelia Parker, Richard Wright, Smith | Stuart and John McCracken, at which time we worked with the Edinburgh Art Festival to install his illuminated light sculptures made of coloured plastic bottles in sites around the city, including an enormous ‘Candela’ in the glasshouse of the Botanic Gardens. We worked together in a number of other projects and publications in the years that followed, but it wasn’t until the summer of 2019 that we made a full exhibition together. My Own Private Bauhaus celebrated David’s long relationship with colour in art through the circle, triangle and square, often utilising what he calls the ‘found’ colour of the modern city - the colourful pleasures of things that others relegate or dismiss – the plastic produce of pound shops, or the recycled off-cuts of contemporary life.

-

David BatchelorConcreto 5.0/01, 2022concrete and coloured glass31 x 50.5 x 6 cm

David BatchelorConcreto 5.0/01, 2022concrete and coloured glass31 x 50.5 x 6 cm

12 1/4 x 19 7/8 x 2 3/8 in -

2020

And so came 2020, the year of the pandemic, and like our colleagues in galleries around the world we had to pause our programme and think about how best to work with artists in a world without walls. Our response was an online project, delivered daily via our website and instagram in which one work led to another in a kind of continual sequence. We called it The Unseen Masterpiece, a bastardisation of Balzac’s title for an exhibition that would never exist. It kept us going. Eventually, amidst the stop start of opening and closing the gallery we were able to host our first exhibition with Caroline Walker.

Caroline’s subject, a continuation of her interest in women in working environments, was her mother Janet going about her daily household chores. It was a deeply personal and intimate tribute, a kind of extended love letter to the idea of home, at a time when our understanding of what home means had changed so much. Janet continues as a subject, and Caroline made this newest painting specifically for this celebratory exhibition, noting, touchingly, the comparison between a gardener’s nurturing of plants and a gallery’s relationship with its artists.

-

Caroline WalkerCovering, Late Evening, June, 2022oil on linen235 x 180 cm

Caroline WalkerCovering, Late Evening, June, 2022oil on linen235 x 180 cm

92 1/2 x 70 7/8 in -

2021

In 2004 we saw an exhibition of portrait miniatures by Moyna Flannigan at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery. They were intense and slightly strange little paintings, almost humorous yet haunting. We bought two. Moyna’ s exhibiting career progressed alongside a teaching career at Glasgow School of Art, showing regularly in Europe and America and tutoring a new generation of artists from Scotland, including Caroline Walker.

We lost sight of her for a few years, but one afternoon in 2018 we walked into a room at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and were stopped in our tracks by a blend of collage and painting that felt like something entirely new. Moyna’s figures are an amalgam of memory and experience, in which fragments from art history, mythology and popular culture combine to explore ideas of power and vulnerability in the representation of women. We made our first show together Matter in 2021.

-

Moyna FlanniganAriel, 2022distemper on linen60 x 45 cm

Moyna FlanniganAriel, 2022distemper on linen60 x 45 cm

23 5/8 x 17 3/4 in -

2022

In writing about Andrew Cranston, we noted that the way a gallery meets artists is always interesting. We were in Andy’s Glasgow studio one day when he mentioned that there was another artist working next door that we ought to look at. We did, and so met Lorna Robertson. Andy and Lorna are life partners as well as studio neighbours. Over their early careers they both exhibited from time to time, but with Andy teaching three days a week at Gray’s Schools of Art in Aberdeen and Lorna balancing studio time with looking after their three sons, they were for many years each other’s principal audience, greatest supporters and harshest critics.

Working with this enormously talented artist couple in the moment that their works finally get the attention they deserve has been a highlight of the gallery’s recent history, and Lorna’s exhibition for last summer’s Edinburgh Art Festival was a moment of joy. Her work for Twenty-Five continues her very personal investigation of what it means to make paintings in the present day, paintings that are layered with reference and meaning, but which above all are about the idea of painting itself.

-

Lorna RobertsonYourself, myself , 2023oil on canvas69 x 69 cm

Lorna RobertsonYourself, myself , 2023oil on canvas69 x 69 cm

27 1/8 x 27 1/8 in (framed) -

Twenty-Five is installed across the whole of our building in Edinburgh and includes works by many other artists close to the gallery. They are: Roger Ackling; Ben Cauchi; Jessica Harrison; Marine Hugonnier; Ellsworth Kelly; Brandon Logan; Jonny Lyons; Andrew Miller; Craig Murray-Orr and Oana Stanciu. Our thanks to everyone involved.

Richard and Florence Ingleby, 27th January 2023

-

-

Jonny LyonsComes and goes (A comma that changes everything) , 2022Giclée print on Hahnemühle 308gsm Photo Rag Acid-free Archival Paper

Jonny LyonsComes and goes (A comma that changes everything) , 2022Giclée print on Hahnemühle 308gsm Photo Rag Acid-free Archival Paper

Edition of 10. This is 1/10121.8 x 91.3 cm

48 x 36 in (framed) -

Jonny LyonsYou'll never paint that flower (A comma that changes everything), 2022Giclée print on Hahnemühle 308gsm Photo Rag Acid-free Archival Paper

Jonny LyonsYou'll never paint that flower (A comma that changes everything), 2022Giclée print on Hahnemühle 308gsm Photo Rag Acid-free Archival Paper

Edition of 10. This is 1/10121.8 x 91.3 cm

48 x 36 in (framed)

-

-

Brandon LoganPartial Fancy, 2022Acrylic and string81 x 108 cm

Brandon LoganPartial Fancy, 2022Acrylic and string81 x 108 cm

31 7/8 x 42 1/2 in -

Marine HugonnierView of Chile / Chile's Acidic Soil Medium, 1879 / 2020Oil on millboard with two condition reports59 x 68 cm/ 23 1/4 x 26 3/4 in (painting framed)

Marine HugonnierView of Chile / Chile's Acidic Soil Medium, 1879 / 2020Oil on millboard with two condition reports59 x 68 cm/ 23 1/4 x 26 3/4 in (painting framed)

46 x 36.8 x 4 cm / 18 1/8 x 14 1/2 x 1 5/8 in (report, framed each -

Andrew MillerQuarter Cut, 2021coloured electrical tape on a found piece of fake wooden panel109 x 50 cm

Andrew MillerQuarter Cut, 2021coloured electrical tape on a found piece of fake wooden panel109 x 50 cm

42 7/8 x 19 3/4 in -

-

Jessica HarrisonRoyal Doulton Figure - Danielle HN 3001, 2017Found ceramic, glaze12 x 8.5 x 19cm

Jessica HarrisonRoyal Doulton Figure - Danielle HN 3001, 2017Found ceramic, glaze12 x 8.5 x 19cm -

Jessica HarrisonRoyal Doulton Pretty Ladies Figurine - Summer HN5322, 2017Found ceramic, glaze15 x 15 x 22cm

Jessica HarrisonRoyal Doulton Pretty Ladies Figurine - Summer HN5322, 2017Found ceramic, glaze15 x 15 x 22cm -

Jessica HarrisonRoyal Doulton Figurine Belle Figure of Year 1996 HN3703, 2017Found ceramic, glaze14.5 x 11 x 21.5cm

Jessica HarrisonRoyal Doulton Figurine Belle Figure of Year 1996 HN3703, 2017Found ceramic, glaze14.5 x 11 x 21.5cm -

Jessica HarrisonCoalport Ladies of Fashion Figurine Phillipa, 2017Found ceramic, glaze15 x 18 x 20.5cm

Jessica HarrisonCoalport Ladies of Fashion Figurine Phillipa, 2017Found ceramic, glaze15 x 18 x 20.5cm

-

-

Installation view of the Feasting Room, Ingleby, Edinburgh, 'Twenty Five', 2023. Photo by John McKenzie

Installation view of the Feasting Room, Ingleby, Edinburgh, 'Twenty Five', 2023. Photo by John McKenzie -

Installation view of the Feasting Room, Ingleby, Edinburgh, 'Twenty-Five', 2023. Photo by John McKenzie.

Installation view of the Feasting Room, Ingleby, Edinburgh, 'Twenty-Five', 2023. Photo by John McKenzie.

Twenty-five

Past viewing_room